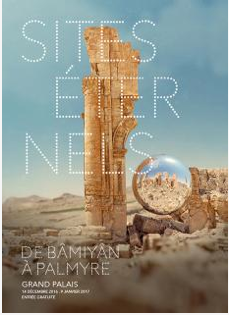

According to UNESCO the six World Heritage sites in Syria have been damaged, pillaged or completely destroyed. With stunning 360 degree panoramic 3D visuals the « Eternal Sites » exhibition (until January 9, 2017) virtually revisits four major archaeological sites: Khorsabad (Iraq), Palmyra (Syria) the Great Mosque of Damascus (Syria) and the Kerak Crusader Castle (Syria). Continuer la lecture de « Eternal Sites at Grand Palais »

According to UNESCO the six World Heritage sites in Syria have been damaged, pillaged or completely destroyed. With stunning 360 degree panoramic 3D visuals the « Eternal Sites » exhibition (until January 9, 2017) virtually revisits four major archaeological sites: Khorsabad (Iraq), Palmyra (Syria) the Great Mosque of Damascus (Syria) and the Kerak Crusader Castle (Syria). Continuer la lecture de « Eternal Sites at Grand Palais »

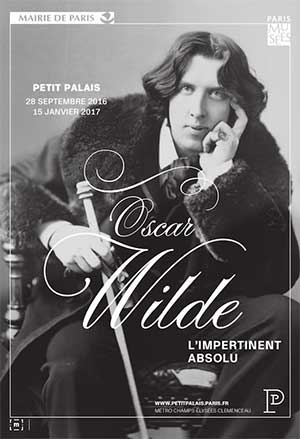

Oscar Wilde at Petit Palais

« They say that when good Americans die » Oscar Wilde once said « they go to Paris… » Graffiti scribbled on Wilde’s tombstone in Pere Lachaise cemetery says « Here lies the greatest man who ever lived. » Maybe not the greatest as some of his fans think, but Wilde certainly was among the most clever. His aphorisms still bring a smile. For example about life he philosophized: « There are only two tragedies in life: one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it. » Continuer la lecture de « Oscar Wilde at Petit Palais »

« They say that when good Americans die » Oscar Wilde once said « they go to Paris… » Graffiti scribbled on Wilde’s tombstone in Pere Lachaise cemetery says « Here lies the greatest man who ever lived. » Maybe not the greatest as some of his fans think, but Wilde certainly was among the most clever. His aphorisms still bring a smile. For example about life he philosophized: « There are only two tragedies in life: one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it. » Continuer la lecture de « Oscar Wilde at Petit Palais »

Christmas Markets in Paris 2016

Paris’ Christmas markets are among the things that make the holiday special in this city. The markets are found all over the city from the stunning display on the elegant Champs Elysee to the Place Saint Sulpice to the Trocadero. But the biggest (10,000 meters) and most diversified market (200 stalls) is found at Paris’ La Défense.

Paris adopts a German tradition

The earliest Christmas markets date back to the late middle ages and have their origin in Germany. The Dresden « Striezelmarkt » is said to be the oldest Christmas market and was first held in the 15th century. The Bautzen Christmas market and the Vienna « December Market » are supposed to be even older dating back to the 13th century. It was in 1570 when the Christmas market tradition found its way into Alsace, France’s easternmost region bordering Germany. Continuer la lecture de « Christmas Markets in Paris 2016 »

French Holiday Wines with sparkle…

Twelve Bubbly Days of Christmas…. Holidays are times to uncork a bottle of bubbly and make a toast. Although France’s champagne is the world’s most famous celebratory drink there are others that merit tasting. Since there are twelve days of Christmas here are a dozen bubblies to get you in the spirit this season.

Champagne is the name for sparkling wine from the famous eponymous region of France associated with it. By law, no other effervescent beverage may be called champagne! This process begins with taking various still wines and blending them to make a cuvée that represents the style of a winery or champagne house. A complex cuvée can consist of as many as 30 to 40 different wines. The percentage of sugar in the shipping dosage added at the end determines the degree of sweetness in the final wine. From most dry to sweetest, sparkling wines are classified as BRUT, EXTRA DRY (or extra-sec), SEC, DEMI-SEC, or DOUX

Day 1 Starting light. Laurent-Perrier Ultra Brut is not only Ultra Dry but also ultra-light with only 65 calories per glass! It is champagne in its purest form, without the final addition of sugar that is made to all other champagnes just before the bottle leaves the cellars. Its delicate finish and honeysuckle nose make it a good match if you are serving seafood to your guests, especially caviar and oysters. This champagne is a blend of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, which come exclusively from grapes from very ripe harvests. Lavinia, 3-5 bd de la Madeleine, 1er http://www.lavinia.fr

Day 2 Sparkling wines from France’s Alsace region must be aged for a minimum of 9 months. The grapes allowed in these wines include auxerrois blanc, pinot blanc, pinot gris, pinot noir and riesling. The quality of the Crémant d’Alsace wines, which are made using the méthode champenoise, is generally quite good, although they’re a bit more expensive than some of the other non-champagne alternatives. Julien, caviste, 50 rue Charlot, 3e

Day 3 The appellation Crémant de Bourgogne is the generic term for sparkling wines of all colors from the Burgundy region. Every grape variety grown in Burgundy is allowed in the crémant, although Gamay may not constitute more than 20% of the blend. A dry and elegant example with vanilla biscuit aromas is L.Vitteaut-Alberti Brut. Blanc de Blancs (chardonnay). Julien, caviste, 50 rue Charlot, 3e

Day 4 The Blanquette de Limoux is the world’s oldest sparkling wine, and while the good-quality blanquette was appreciated by the winemakers of the local coopérative Sieur d’Arques, they wanted to make a sparkling wine that rivaled champagne. The result is their excellent Crémant de Limoux. The large portion of chardonnay grapes and Chenin grapes gives finesse to the crémant. This one is traditionally bottle fermented and is produced from the vines of chardonnay (20%), chenin (20% max.) and Mauzac. Lavinia, 3-5 bd de la Madeleine, 1er

Day 5 Ring in the 5th day of Christmas drinking, with French organic wine La Taille aux Loups. The sensual experience of this wine begins with the label. It’s black, velvety-to-the-touch with yellow and mauve writing. Petillant naturel non dosé refers to the fact that the wine was made with the méthode champenoise but without sugar or dosage added. The bubbles were formed naturally with their own sugars. The yeasts in this wine were not added but rather are naturally occurring in the skins. The wine is from the appellation Mont Louis in the Loire Region where the soils contain clay, limestone, and sand. The minerality of this 100% chenin wine makes for a refreshing aperitif that pairs wonderfully with seafood hors d’œuvres. Julien, caviste, 50 rue Charlot, 3e

Day 6 Just like the gifts under your tree, sometimes the packaging is half the joy! Crack open a cold one with « Fun en bulles, » it has a beer cap rather than a cork with wire. The label informs you that this wine was harvested in « thongs » by winemaker Didier Beauger, a man described in the wine industry as an extra-terrestrial. He calls his effervescent wine « vin turbulent »! For his « Fun en bulles, » he uses the cépage (varietal) clairette. La Crèmerie, rue des Quatres Vents, 6e

Day 7 Not seven swans a-swimming but an effervescent wine from the Rhône valley. With the designation Vin de Table de France, Gramenon Tout en bulle is made in the most northern sector of the southern Rhône with the clairette grape by producer Michèle Aubéry-Laurent, known for achieving wines of extreme purity and fruitiness as a result of a totally organic approach. Lavinia, 3-5 bd de la Madeleine, 1er

Day 8 Eight turtledoves can fly us to Italy for some Muscato d’Asti La Spinetta, 2004. My personal Italian favorite, a sweet sparkling white that is low in alcohol (5.5%) and makes a great aperitif or accompaniment to a fruit dessert. From the region of Asti; the winemaker is the famous Georgio Riveti, and it’s made with 100% moscato d’asti grapes. Lavinia, 3-5 bd de la Madeleine, 1er

Day 9 Lambrusco is not an Italian Sports car, though it is red. It’s the perfect wine for an afternoon gathering – light, flavorful, zesty, and low in alcohol, about 11%. Its aromatic bouquet can vary from fruity with pleasant vinous to floral overtones, plus hints of violet and heather. One important thing to keep in mind is that Lambrusco can be either dry or sweet. Secco means dry, while Amabile means sweet. At Italian grocery stores throughout Paris

Day 10 Prosecco, the very word hints at the dryness in this sparkling wine that is a refreshing accompaniment to sliced meats, and hard cheeses. Prosecco is a variety of white grape grown in the Veneto region of Italy, and also gives its name to the sparkling wine made from the grape (grown in the Conegliano and Valdobbiadene wine-growing regions north of Venice). Its late ripening has led to its use in dry sparkling (spumante) and semi-sparkling (frizzante) wines, with their characteristic bitter aftertaste, which calls for food pairing. Julien, caviste, 50 rue Charlot, 3e

Day 11 Olé! Off to Spain’s Catalonia for some Cava, which is a famous sparkling wine from this much-visited wine region. The grapes Xarel-lo and Parellada are Spain’s native varieties. Well adapted to producing acidic wines despite the hot weather, these grapes make Cava fresh and well-balanced. Because Cava is dry, it can be enjoyed before, during and after the meal. Lavinia, 3-5 bd de la Madeleine, 1er

Day 12 Surprise your guests with a new world bubbly! Krone Borealis from South Africa is a sparkling wine named after the constellation of stars. Grapes are handpicked under the stars in the cool of the night to retain flavor and aroma. A little poetic license might be used to describe this sparkling wine, which is full of « stars. » Krone Borealis Brut MCC is a bottle-fermented sparkling blend featuring 50-50 chardonnay and pinot noir with no added preservatives. The Krone Borealis viticultural estate boasts the first underground sparkling wine cellar in Africa. Lavinia, 3-5 dd de la Madeleine, 1er

Montmartre fetes its wine Oct 7-11

That the Butte’s wine is almost undrinkable has never gotten in the way of what has to be one of this capital’s best annual fests!

As with any good party, this one has something for everybody: it’s part folklore, with fraternal orders from the winegrowing regions of France turning out in traditional robes and quirky hats, and part Arbor Day parade, complete with Harvest Queen, marching bands and street theater.

Paris’ grape-picking tradition, dates back to the time of Asterix. Admittedly, the vine hit some hard times along the way. Most notably, a 200-year hiccup that began when the 1st-century Roman Emperor Domitian forbade vineyards in Gaul. Whether this was because he felt that the indigenous population was getting a bit too merry – or, because Italy’s wine merchants didn’t need the competition – is a matter of dispute…

It wasn’t until the 3rd century that the Gauls were able to replant their vine stocks. By the next century, Lutetia (ancient Paris) had become one of the four winegrowing capitals of Gaul, along with Bordeaux, Narbonne and Trèves.

Paris vintages had their heyday during the Middle Ages, when they were exported to Picardy, Normandy and even England. The wines of Montmartre (or Mont Mercure, as it was then known) were particularly favored. One of them, La Goutte d’Or, was called the « king of wines. »

By the 17th century, apartment construction threatened the city’s grape-growers. And, come the mid-1800s, the poet Gérard de Nerval lamented, « Every year this humble slope loses another row of its scrawny vines down a rock quarry…

Farewell harvest baskets! Farewell grape harvests! Tomorrow houses will grow here instead of grapes. » By WWI the last vestige of Montmartre’s once-plentiful vineyards was no more. Enter Poulbot. Francisque Poulbot was a Montmartre artist, known for his paintings of chubby street urchins. In 1930 he mobilized the population of the Butte against developers planning to build on the vacant portion of land bordering the famous cabaret Au Lapin Agile. Poulbot and company occupied the site and proclaimed it their « Liberty Square » – three years later, the city of Paris planted vine stocks there.

In 1934, the intrepid mayor of Montmartre, Pierre Labric, created the fête du vin, conveniently overlooking the fact that it would be at least 10 years before the vines produced the least yield. Fortunately winegrowers in the provinces agreed to provide some 30 tons of grapes to get production rolling, and by the 1940s the Montmartre vineyard was elaborating its own nectars.

Today the quartier produces about one ton of Gamay noir (with white juice), Pinot noir and Landay grapes (thick-skinned and acidic owing to the vines’ location on the north slope of the Butte), enough for about 700 bottles of Le Clos Montmartre rosé wine. The actual harvesting is done by a handful of workers from the City of Paris’ parks and gardens department, and doesn’t always coincide with the date of the festival. The pressing of the grapes, carried out on the place du Tertre during the 1940s, now takes place in a specially designated « cave » belonging to the 18th arrondissement’s town hall. JC

This year the festival will be held October 7-11

Still Standing Tall

Did you hear the one about the lady who married the Eiffel Tower? No, really. Erika La Tour Eiffel had had other infatuations with objects, including Lance, the bow with which she became an archery champion, and the Berlin Wall. But, now in her late 30s, she tossed those over and promised to love, honor, and obey the tower in an intimate ceremony in Paris. She duly changed her name to reflect her marital status. A photo showed the smiling, comely newlywed hugging her riveted husband, who maintained a dignified reserve. Admittedly, said Erika, there is a bit of a problem in the marriage: “The issue of intimacy, or rather lack of it.”

Did you hear the one about the lady who married the Eiffel Tower? No, really. Erika La Tour Eiffel had had other infatuations with objects, including Lance, the bow with which she became an archery champion, and the Berlin Wall. But, now in her late 30s, she tossed those over and promised to love, honor, and obey the tower in an intimate ceremony in Paris. She duly changed her name to reflect her marital status. A photo showed the smiling, comely newlywed hugging her riveted husband, who maintained a dignified reserve. Admittedly, said Erika, there is a bit of a problem in the marriage: “The issue of intimacy, or rather lack of it.”

Maybe Erika fell under the tower’s spell. Hearts beat faster there, as evidenced by a physiological study done the year it was built. The savants noted that, “On rising by elevator to the third platform, the pulse beats faster, and, especially in women, there is a psychic excitement that is translated by gaiety, animated and joyous conversation, laughter, and the irresistible desire to go still higher—in sum, a general excitement.” The people at the TripAdvisor website concur that it inspires romance. After in-depth study, they concluded that the Eiffel Tower is the number-one place in the world to propose.

Okay, Erika does live in San Francisco, and maybe this, as the French expression has it, explains that. But the Eiffel Tower has indeed stirred strong emotions ever since its construction for the great Paris World’s Fair of 1889. To start with, many in this hidebound country were scandalized by something so daring and, well, different. In 1888, with the tower rising to its ultimate height of 1,000 feet faster than seemed possible, some 40 self-appointed arbiters of taste, including the composer Charles Gounod and the writer Guy de Maupassant, signed a strident petition protesting against “the erection in the heart of our capital of the odious column of bolted metal.” Maupassant in par- ticular later sulked that he left Paris because of “this tall, skinny pyramid of iron ladders.”

But the public, then as now, loved the tower. Nearly 2 million visited it during the fair. Not only the great unwashed, but also the likes of the Prince of Wales, the king of Greece, the shah of Persia, and Archduke Vladimir of Russia, not to mention Buffalo Bill Cody. An impressed Thomas Edison rode the elevator to the top and presented Gustave Eiffel, who had a small apartment there (where it’s said he entertained certain Belle Époque belles), with the first phonograph recording of La Marseillaise. Edison dedicated it to “Monsieur Eiffel, the Engineer, the brave builder of so gigantic and original a specimen of modern Engineering.”

The crowds kept coming. Over 200 million have visited it since its construction. Today it is the most frequented and, statistics show, most photographed monument in the world, with about 7 million paid visits a year. In France it easily tops the Arch of Triumph, Notre Dame Cathedral, the châteaux of the Loire Valley, and Mont Saint-Michel in Nor- mandy. It also outdraws comparable attractions in the U.S. such as the Washington Monument and the Statue of Liberty.

Still more crowds will be attracted by this summer’s celebrations for the tower’s 120th anniversary, which is being marked by special exhibits at the Paris city hall and on the second platform of the tower itself. Coincidentally it is getting a new paint job, with 25 men, nimble employees of a Greek company that specializes in painting ships and smokestacks, clambering among its girders to brush on some 60 tons of paint in the subtle shade known as Eiffel Tower Brown. (Fortunately, past French newspaper campaigns in favor of a patriotic tower resplendent in tones of bleu-blanc-rouge never got off the ground.)

My own epiphany occurred one evening when I took a stroll on the Champ de Mars, not far from my home in Paris. I found myself beneath the Eiffel Tower and glanced up. Above me the gigantic, intricate tracery of crisscrossing girders soared more majestically than the columns and vaults of any Gothic cathedral. I was held, fascinated—awestruck is not too strong a word. And I was reminded of Eiffel’s rebuttal to those who complained that his tower would be ugly: “There is an attraction and a charm inherent in the colossal that is not subject to ordinary theories of art,” he insist- ed. “The tower will be the tallest edifice ever raised by man. Will it not therefore be imposing in its own way? I believe that the tower will have its own beauty.”

Artists, poets, and philosophers eventually came to agree with him. The tower has been the subject of paintings by Chagall, Dufy, Picasso, Utrillo, Van Dongen, and other icons of modern art. Poets and writers like Guillaume Apollinaire, Jean Cocteau, and Jean Giraudoux have rhapsodized about it. Among philosophers, Roland Barthes, grand panjandrum of structuralism in European and American universities, has done more high-flown double- doming about the tower than any other, devoting an entire book to analyzing it. The tower eludes reason and becomes the ultimate symbol, he posits, by being “fully useless.” For him it is “the inevitable sign, for it means everything.”

EVEN IF IT DOESN’T quite mean everything, the tower often has meant outlandish stunts. The harebrained antics began in 1891 when a Paris baker wobbled up the 347 steps to the first platform on stilts, only to be topped later by a clown named Coin-Coin who bumped down them on a unicycle. Philippe Petit, the tightrope walker who made it between New York’s Twin Towers, walked a wire for nearly 800 yards from the Trocadero across the Seine to the second platform to celebrate the tower’s centenary in 1989.

Naturally we Americans wanted in on the fun. When Charles Lindbergh approached Paris to complete the first transatlantic flight on May 21, 1927, he homed in on “a column of lights pointing upward.” Despite his fatigue, he couldn’t resist playfully circling the tower before landing the Spirit of St. Louis to a hero’s welcome at Le Bourget. Only a few days after American (sorry, I meant French, of course) troops liberated Paris and the tricolor again floated above the tower, a B-17 Flying Fortress of the U.S. Army Air Corps zoomed deftly between its legs. Later, Arnold Palmer drove a golf ball off the second platform, getting extra hang time. A former Marine pilot who had flown 824 missions over Vietnam aimed a Beechcraft Bonanza down the Champ de Mars and zipped under the tower. Nowadays terrorist crazies have even bigger stunts in mind: intelligence intercepts show the tower is high on the list of things al Qaeda wannabes would love to blow up.

The loss to the world’s heritage would be great, for the tower represents a unique achievement. Several 1,000-foot towers had been proposed by 19th-century engineers to show off their growing technical prowess, notably for London in 1833 and Philadelphia in 1876. Those were never realized, but Eiffel, arguably the greatest engineer of the century, showed it could be done. Working at the forefront of the technology of the age, the man the French call le magician du fer had already built iron structures like train stations and railway bridges, including the highest viaduct in the world, from France to Russia, South America to Indochina. In a spare moment he had also tossed off the internal iron skeleton of the Statue of Liberty.

Eiffel based everything on meticulous pencil- and-paper calculations, with particular attention to wind force. Working from more than 5,000 mechanical drawings, he had the tower’s massive stone foundations, 15,000 girders, and 2.5 million rivets in place in just over two years with no loss of life—the Brooklyn Bridge, completed in 1883, took 14 years and some 20 lives, including that of its designer, John Roebling—and 6 percent under budget. It would be hard to duplicate the feat today.

It was only in 2004 that two American mathematicians finally broke the complex mathematical code for the tower’s shape that keeps it standing tall. It is, they say, a nonlinear, integro-differential equation yielding an exponential profile. Eiffel had figured that out in his head 120 years ago.

About the Author

Joseph A. Harriss is The American Spectator’s Paris correspondent. His latest book, An American Spectator in Paris. Info: http://www.unlimitedpublishing.com/amspec/

Tasty tips…French aperitifs

Terrace weather is here and having a drink at a strategically placed people-watching café is one of the pleasures of living in Paris. Here are some tips on some of France’s favorite after-six drinks.

Terrace weather is here and having a drink at a strategically placed people-watching café is one of the pleasures of living in Paris. Here are some tips on some of France’s favorite after-six drinks.

Dubonnet

A bitter aperitif invented in Paris in 1846 by Joseph Dubonnet. Dubonnet is made from wines from Roussillon, plant extracts and the bark of quinine, a South American tree introduced into Europe in the 17th century by Spanish missionaries. Its flavor is very sweet, fruity, resembling blackcurrant. The original recipe is 14.8% alcohol per volume but another red Dubonnet and a white Dubonnet at 19% alcohol per volume were created for the American market. It can be enjoyed straight or in a cocktail.

Vermouth

An apéro obtained by the flavoring of a mixture of wine (75% minimum) and neutral alcohol with plant extracts like absinthe (in red vermouth), and artemisia (in white vermouth). It has between 14.5 and 22% alcohol. There are several different types of vermouth, dry vermouth (50 to 60g of sugar/L), which is clear, and rosso vermouth (100 to 150g of sugar/L), which is sweeter and caramel colored. Noilly Prat is the most commonly known commercial brand of French Vermouth. Italy produces the Martini and Cinzano.

Campari

Campari is an Italian bitter. It can be enjoyed straight or in cocktails, the most famous being the Americano, created in 1917 in honor of the American soldiers who defended Europe. For an Americano, just add vermouth and fizzy water.

Pineau des Charentes

The Charentes, a department in central France named after the Charente river, is famous for Cognac and Pineau. Pineau was invented when a winemaker in the Charentes poured grape must accidentally into a barrel containing cognac. It is a sweet strong wine.

Lillet

Lillet is an aperitif produced in Podensac (a commune in the Gironde department) since 1887. Red or white, it is made through the maceration of quinine bark and plants in a mixture of citrus fruit extracts, noble wines and cognac. It is then aged in oak barrels.

Byrrh

First sold in pharmacies because of its healing qualities, Byrrh was created in 1870 in Thuir, in the western Pyrenees, from carignan and grenache wines and flavored with various spices.

Suze

Suze is an aperitif based on the maceration in alcohol of gentiane roots from the Auvergne, citrus flavors and aromatic plants. It is a bittersweet beverage with a subtle flavor.

Ricard

This summery aperitif became popular when absinthe was banned in France. Unchanged since 1932, its recipe includes anis stars from China and Vietnam, licorice, plants, water, and alcohol. Add Sirop d’Orgeat and you have a Mauresque cocktail. Sirop d’Orgeat is obtained by the cooking of ground almonds in syrup. Water and orange blossoms are often added.

Pastis à l’ancienne

An aperitif rich in flavors and aromats, Pastis à l’ancienne is an anis liqueur with lots of spices (cinammon, badiane, nutmeg, pepper) and herbs from Haute-Provence (sage, armoise, centaurée). After maceration, the product is either distilled or filtered. Caramel may be added. According to European Economic Community standards, the anethol content (aromatic substance of anis) of pastis must be at least 1.5g and a maximum of 2g per liter.

Get 27

A liqueur made from spearmint, alcohol, water and sugar, it was named after its creators Jean et Pierre Get, and is called Get 27 or Get 31, according to its percentage of alcohol content.

Woody Allen discusses « Cassandra’s Dream »

Woody Allen’s film « Cassandra’s Dream » is a story of death and guilt set in contemporary London. It tells the tale of two brothers (Ewan McGregor, Colin Farrell) who while attempting to improve their miserable lives fall into dire straits with predictable unfortunate consequences. The film premiered at the Venice Film Festival where Woody Allen made the following comments.

« My movie is a story of two young people who because of their weaknesses and their ambitions end up in a tragic situation. They mean well, but it turns out that events and their own actions bring them to a tragic end. Unconsciously, the story is inspired by much of the mythology and biblical references I grew up reading.

Why a murder? Murder is a fundamental staple of drama. Murder has been used for centuries. I am interested in the possibility to be either Cain or Abel.

Guilt is a tragic part of life. When the topic is serious, the perspective on guilt becomes quite serious. My characters are obsessed with guilt, riddled by guilt. My hero in this film is ready to carry out the deed with his uncle. But he has his own agenda, if he is honest with himself. It is fascinating and tragic: two men from the same background approach the same event so differently. I was obsessing with guilt in a comic way.

Life is tremendously tragic, but it has comic moments, moments of pleasure. But basically life is tragic. I am a tragic writer but my most obvious strengths were comic. I always wanted to work on tragic things and my feeling about life is pessimistic. But I think there are extremely amusing oases in that morass.

Oddly I have been influenced by my colleagues, Scorsese, Copolla, Altman, Spielberg, but I never see any of my influences on anyone!

And Scarlett Johansson? She is a wonderful actor, she has no limit on her future. She is young and beautiful and gifted. »

Woody Allen performs with the New Orleans Jazz Band a special concert Dec 25th (3pm, 8pm) at the the Theatre du Chatelet. Info: http://chatelet-theatre.com

Cara Black’s Paris Murders

Leafing through a book behind a pillar in the American Library in Paris, mystery writer Cara Black seemed herself a bit of a private investigator uncovering clues far from the prying eyes of the crowd. Moments later she would give a presentation on her inspiration, her research, and the development of her much-abused yet still youthful protagonist Aimée Leduc, the hero of her thirteen mystery novels all set in Paris. And from talking with Black about her craft, it becomes clear that she puts together books the way Aimee Leduc uncovers mysteries.

« My stories come from place and setting, » she says before relating what has now, after thirteen books in the enormously successful Aimée Leduc series, become something of a ritual for her – the yearly hunt for the next perfect Paris scene. « I go to places like the Marais, like the Clichy, and try to find those spectacular areas a little off the beaten path that Paris is famous for, the places that you have to search a little bit to get to. And when I find them, that’s where the stories start. » Black has made Paris her literary bread and butter, with each of her mysteries tackling the sights, sounds, and textures of a different Parisian arrondissement.

But far from being assembly line products, the books in the Aimée Leduc series are all painstakingly researched, having been lauded by audiences and critics alike for their attention to detail and their quirky originality. « Paris is an unforgiving muse, » says Black, « because when one writes about Paris, there’s no room for error. » Paris has always been a bit of a literary double-edged sword, with a well-known tradition of expat writers offering their personal takes on the city.

The success of such English-language luminaries as George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway in famously evoking the city makes it a difficult task for any writer to tackle. Black is undaunted, however, explaining the relaxed perspective she brings to her writing. « It was Benjamin Franklin who said that all Americans have two countries: America and France, » she begins. « When I first started it was clear to me that I couldn’t write as a Frenchwoman – I can’t even tie my scarf like a Frenchwoman – but that I could write as an outsider. » So Black created a character that is a modest fantasy for any American infatuated with Paris – her heroine, Aimée Leduc, is not wholly Parisian but half-American and half-French, and her job is to wander the streets of Paris searching for clues. But best of all, Black gushes, « she lives in a fabulous apartment on the Ile-St-Louis. »

The success of such English-language luminaries as George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway in famously evoking the city makes it a difficult task for any writer to tackle. Black is undaunted, however, explaining the relaxed perspective she brings to her writing. « It was Benjamin Franklin who said that all Americans have two countries: America and France, » she begins. « When I first started it was clear to me that I couldn’t write as a Frenchwoman – I can’t even tie my scarf like a Frenchwoman – but that I could write as an outsider. » So Black created a character that is a modest fantasy for any American infatuated with Paris – her heroine, Aimée Leduc, is not wholly Parisian but half-American and half-French, and her job is to wander the streets of Paris searching for clues. But best of all, Black gushes, « she lives in a fabulous apartment on the Ile-St-Louis. »

Black herself clearly envies the life she has created for Aimée Leduc. Her own life, however, is not so far away from that of her heroine’s. As research is key to the success of her books, Black makes frequent trips to Paris to soak up the atmosphere, follow-up on promising leads, and interview anyone she can find – from prostitutes to river workers – that can offer her a glimpse into what really goes on in the dark corners of the city. And Black seemingly has no intention of stopping anytime soon. When asked after her presentation how long she intends to write about Paris for, she answers quickly, rolling her eyes with mock exasperation, « I’ve only got fifteen arrondissements left to go. »

To Tu Or Not To Tu

Politeness, friendliness, and formality at its most French —The French revel in their complications despite the frequent inconvenience of getting tangled in them. For one thing, it confirms their cherished impression that they are unique on earth, a blest condition known locally as the French Exception. For another, it makes everybody else jump through Gallic hoops to do things their way. Even Charles de Gaulle, who occasionally admitted to despising his compatriots as unworthy of his idea of France, asked in a moment of exasperation, « How can you govern a country with over 300 kinds of cheese? »

Politeness, friendliness, and formality at its most French —The French revel in their complications despite the frequent inconvenience of getting tangled in them. For one thing, it confirms their cherished impression that they are unique on earth, a blest condition known locally as the French Exception. For another, it makes everybody else jump through Gallic hoops to do things their way. Even Charles de Gaulle, who occasionally admitted to despising his compatriots as unworthy of his idea of France, asked in a moment of exasperation, « How can you govern a country with over 300 kinds of cheese? »

The complexities range far beyond mere varieties of dairy products. Take the normally simple question of automobile headlights. For decades, French ones were not white, like everywhere else, but yellow. « Much less blinding for oncoming cars, » was the official explanation why foreign visitors had to put yellow covers over their headlights at the border. Then France fell in line with worldwide standards and quietly switched to white. The yellow ones, it turned out, had been after all simply a gratuitous complication-although it did have a certain use as a xenophobic tool that made foreigners, always suspect, easily identifiable at night.

Visiting foreigners are also flummoxed by the labyrinth of French closing days before learning that Thursday is the best day to get things done. An unpredictable number of shops are closed on Monday, depending, maybe, on whether they were open Saturday. National museums shut tight on Tuesday, though an indeterminate number of private ones might just be open. Schools are out on Wednesday but in session on Saturday, neatly blocking any plans parents may have for weekend trips. And Friday? Well, that obviously is the beginning of the weekend in a nation with a 35-hour workweek, so your best bet on Friday is just to try a new sidewalk cafe.

Then there is the problem of what to call an unmarried woman. Anyone with a rudimentary familiarity with French knows that the proper term, from time immemorial, is mademoiselle. Mais non! Many single Frenchwomen, especially those in business or of a mature age, now consider that condescending or sexist. Perhaps borrowing a page from their American feminist sisters, they are adamant about being called madame. The law is no help, being tactfully unclear on that point, while traditionalist notary publics insist that official documents use mademoiselle for unmarried women, executives or not. Then there is the theater, where actresses are uniformly called mademoiselle, even if they are icons like Jeanne Moreau or Catherine Deneuve.

Such pettifoggery is all very confusing, not to say annoying, for those of us who consider simplicity a virtue that lets us get on with more important matters. But of all the complications of French life, none is more perplexing — to foreigners and French alike — than when to use the familiar tu or polite vous form of address. The delicate, often embarrassing question of when to tutoyer a Frenchman is a problem fraught with social peril where one gingerly tiptoes on linguistic eggshells. There are no fixed rules for guidance. Make a mistake and you can become an instant boor, make an enemy, or create a more intimate relationship than you intended. It’s enough to make one nostalgic for the proto-Taliban of the French Revolution. True, they made somewhat excessive use of the guillotine, but at least they decreed that all citizens, being equal, would henceforth use tu in addressing each other.

Alas, that good and useful rule fell by the wayside as the 19th-century bourgeoisie replaced the aristocracy and sought genteel status by using vous in clannish ways that only they could understand. That left most speakers of French insecure, with nothing to go on but fallible instinct and feel. When they can’t figure out which form to use, they have to fall back on turns of phrase, often awkward, that avoid addressing their interlocutor directly. That, of course, can only be a stopgap measure.

IT HAPPENED TO ME RECENTLY when my French sister-in-law came for a visit after a long absence. For the life of me, I couldn’t remember whether we had previously used tu or vous. I had to rely on increasingly gauche circumlocution until I could discreetly query my wife about it. « Oh, I’ve never used tu with her husband and she won’t with you, so go with vous, » came the reply. This, despite long being on family terms with the lady.

As one French linguist, Claude Duneton, explains, « All you have to go by are more or less changing usages. There is no rationale to it, and the possible combinations of what form to use in which situation are infinite, depending on the moment at hand and your individual inclination. That’s one of the charms of our language. » Especially charming, it seems, in certain situations. As Duneton points out, « During intimate moments, the sudden change from vous to tu can deliciously increase eroticism. » (So that is what the bluestocking bourgeoisie has been up to?) Which recalls the old cartoon of two American tourists chatting in a Paris cafe. « And then the most wonderful thing happened, » one girl says dreamily to the other. « He switched from the polite to the familiar. »

But even in France there are sometimes other things to do, like working. And in the office, linguistic confusion generally reigns as everyone tries to sort out how to address each other. In some companies underlings use the respectful vous with their superiors, who themselves use the familiar — and condescending — tu with them. To avoid this, many French firms, especially those in fields contaminated by American mores such as advertising and hi-tech, are trying to loosen up the stiff old hierarchical structures by making the tutoiement permissible, or even obligatory, along with open-neck shirts and casual Friday. Jacques Seguela, vice president of a big Paris advertising firm, never uses any form but tu. « It’s more direct, affirmative and cordial, » he explains. « It creates an atmosphere of complicity. »

But the idea of using the familiar form with someone older or higher placed in the socioeconomic pecking order disturbs France’s old feudal reflexes. (Paradoxically, the French say tu to God but vous to the boss.) It leads some to mutter darkly about pernicious foreign contagion. Complaining of today’s « galloping tutoiement, » Le Figaro attributes this sorry state of affairs to « the influence of Anglo-Saxon manners and an egalitarian vision of society. » One linguist, Jacques Durand, observes sadly that the disappearing vous is another bad sign of leveling in French society. « Some people are even calling each other by their first names, » he notes with a certain refined repugnance.

Thus contradictions and hypocrisy abound. Dignified chaps like members of the august French Academy say vous to each other while at the domed Institut de France, home of the Academie Francaise, even if they have known each other since childhood. Then they switch to tu once they doff their bicorne hats and step outside into the real world.

One group that staunchly holds out against creeping linguistic Americanization is the 20,000 or so families that belong to the former feudal aristocracy and today’s haute bourgeoisie. Here the second person plural among themselves is de rigueur. Their main object in life is keeping up appearances and transmitting inheritances; the affected vous means everyone knows his place, stays within his own class, respects the hierarchy — and keeps everybody else at arm’s length.

This can take bizarre forms. I know one family where Madame, proud bearer of « one of the best names in France, » as she says, uses the distant vous with her children until they obtain their high school diploma. Then, as a treat, she uses tu with them. All the while, the children have been using tu with her. There is also the case of my good friends Jean-Pierre and Marie-Louise. We have known each other for a quarter-century but we still use vous, although they use the familiar with other friends (but vous with their son). I gave up long ago trying to arrive at a rational basis for our verbal relationship.

BUT THOSE SLY MANIPULATORS of the spoken word, politicians, are the greatest virtuosos of the tu-vous conundrum. Among the members of the Communist and Socialist parties, the familiar form is obligatory, reflecting true Marxist comradeship. With conservatives it’s more complicated. Jacques Chirac, while president, used the familiar with his longtime political pals but they replied respectfully with vous. At one point he said tu to his minister of the interior, Nicolas Sarkozy, but vous to Dominique de Villepin, his prime minister, who in turn said vous to Sarkozy.

Since becoming president, Sarkozy has become adept at manipulating journalists by using tu with them whether they like it or not, the equivalent of George Bush’s nicknames. « He makes it hard for me to keep him at the necessary distance to maintain journalistic objectivity, » says one newsman at Le Monde. « He draws us into a closer relationship than we want when trying to cover the Elysee Palace. »

Still, it might be a good sign if ordinary citizens start using tu with him. As one sociologist explains the typical subservient French attitude toward the powers that be, « We use vous with the president because we’re actually still living in a monarchy and you have to respect the king. » Now if Frenchmen begin treating Sarkozy as a citizen-president instead of a monarch, we will know that France is indeed venturing into the terrain — itself complicated enough — of 21st-century democracy.

About the Author

Joseph A. Harriss is The American Spectator’s Paris correspondent. His latest book, An American Spectator in Paris, will be released this fall. Book info: http://www.unlimitedpublishing.com/amspec/